Words are not innocent. They often succeed by failing. This failure of words is manifested when words say something other than what they pretend to say. This saying without saying or simultaneously saying and unsaying using words belongs to the politics of enunciation. The politics of enunciation acquires importance in the context of a handbook of unparliamentary words that cannot be used in the parliament. Jacques Derrida has mocked our common sense view that oversimplifies our ability to get beneath the words and reach the meaning they represent through his method of deconstruction. He has successfully demonstrated the ills of being trapped in what is called representational thinking.

We continue to be haunted by the ghost of Plato when it comes to words. The words are thought to be copies of the meaning or realities that they represent. This means there is a divide between words and meaning. Ferdinand Saussure names this dichotomy between words and reality that they stand for with his terms signifier and the signified. This enslavement to Plato manifests in several ways, especially in our denial of polysemy and acceptance of one word one meaning or the reign of monosemy. This enslavement also reminds us of the picture theory of Ludwig Wittgenstein and indicates our surrender to his dictate that says, ‘ where off we cannot speak there off we keep quite’. This means we impose a kind of infantilization that is willing to choose silence in contexts where our words fail to picture a reality. Maybe we have to admit the complexity of words and their meaning as Wittgenstein himself did in his posthumous work, Logical Investigations.

In place of crass realism, we may have to embrace critical realism that remains open to the many ways we use words as in our speech and writing. Without denying the mediatory role or function of the words, we have the challenge to open ourselves to the invocatory, provocatory as well as constructive power of words. Words, therefore, play a powerful role in our life. They do not just mirror the world to us, they also make our world too.J. L. Austen teaches us this constructive power of words by demonstrating the performative power of the words. The order of Judge or the declaration of being husband and wife by a priest in a marriage ceremony indicates the performative power of the words. As we look at the power of words, we have to agree that we have the challenge to catch the fullness or mystery of reality in and through words. This means words do not just stand for something outside them but they carry the reality that they are standing for in many ways. This is so because the truth of the world is told in and through language.

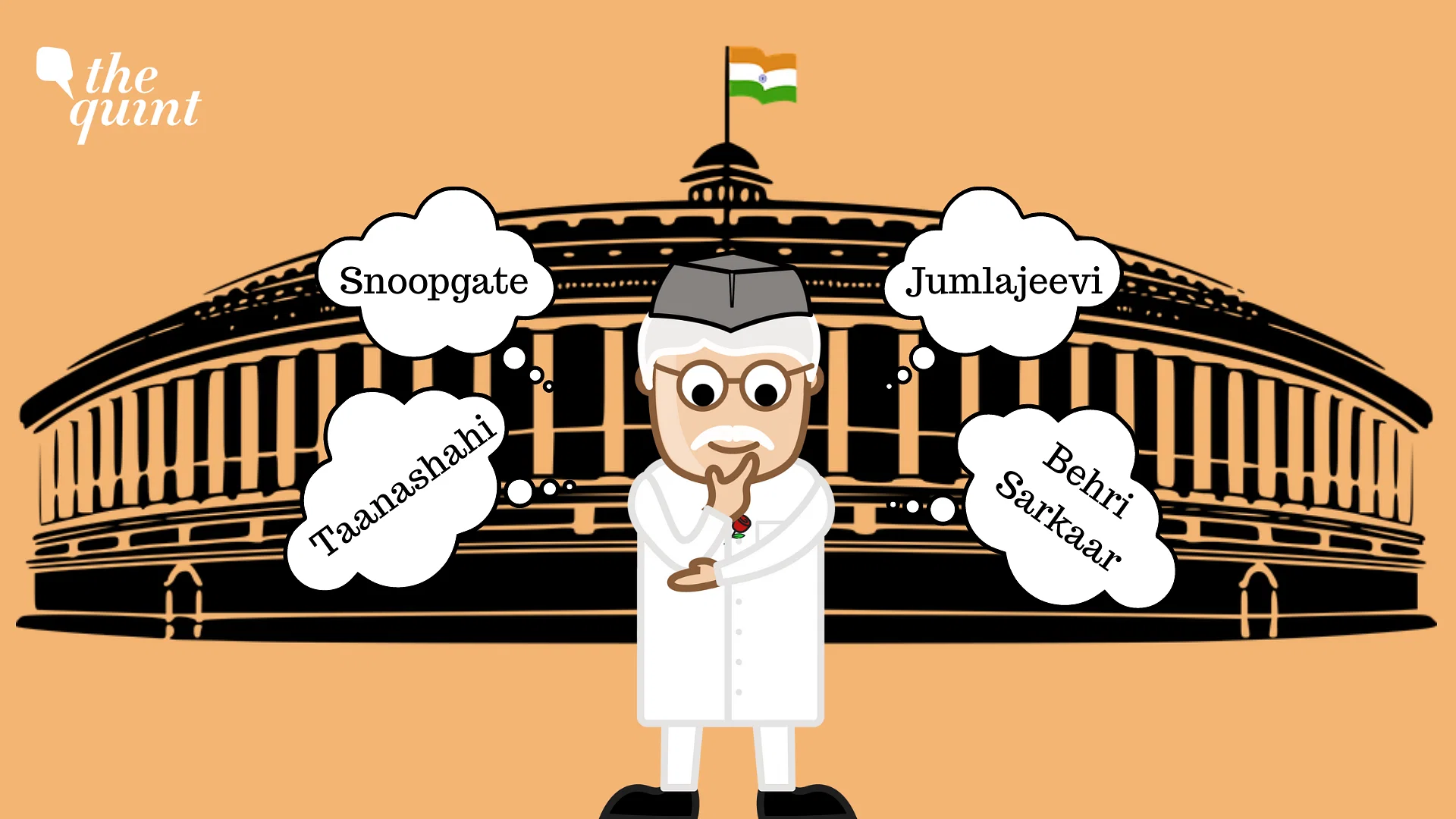

While we appreciate the dazzling power of words, we also have to understand their limits. It is because there are limits to what we can say our words are powerful. The words say and unsay at the same time. This means words exceed what they say as well as transgress the same. This is why words say other things without saying. Hence, the handbook that gags the use of words in our parliament seems to be all set to l fail to gag because words are excessive as well as transgressive. They say and unsay at the same time. This is why one may say to a powerful leader: ‘you are the only good leader in the parliament’ and mean exactly its opposite. The context and the effect with which we say and hear the words control the meaning of our words. Hence, the handbook of a list of unparliamentary words appears to be a vain exercise.