The slogan “Viva Portugal” embodies a rich yet fraught intertextuality, weaving together multiple, often contradictory voices from Portugal’s historical, cultural, and political discourses. At its core, it is a straightforward exclamation of affection—”Long live Portugal!”—rooted in the Romance-language tradition of using the subjunctive “viva” to invoke longevity, prosperity, and vitality for a nation, leader, or ideal. This form echoes across contexts: from cheers at football matches celebrating Cristiano Ronaldo or the national team, to historical invocations during Portugal’s own revolutionary moments. In the republican revolution that ended the monarchy, or more vividly in the Carnation Revolution that toppled the long-standing dictatorship, similar cries of “Viva Portugal!” or “Viva a Liberdade!” rang out as affirmations of freedom, democracy, and anti-authoritarian triumph. Under the authoritarian regime that preceded the revolution, however, the phrase could equally serve nationalist unity, bolstering colonial wars in Africa and Asia while suppressing dissent at home. These overlapping echoes already introduce contradiction: the same words could rally liberators in one era and affirm oppressors in another.

In the specific context of Goa, the slogan’s intertextuality deepens and fractures further. Portugal’s presence in Goa spanned 451 years, from the early conquest until India’s military operation in 1961. For some Goans, especially those with Portuguese ancestry, Catholic heritage, or familial ties to the diaspora, “Viva Portugal” evokes a shared cultural legacy—architecture like grand basilicas, cuisine blending spicy vindaloo and sweet bebinca influences, Konkani laced with Portuguese loanwords, or even modern pathways to Portuguese citizenship and European opportunities. It can signal affection for a distant “mother country” in a globalized world, or simple fandom tied to sports and migration. Yet for freedom fighters and many others, it seems to resurrect memories of exploitation: religious persecution , destruction of temples, economic drain through monopolies, and suppression of local identities in favor of Lusitanization. The 1961 liberation marked a decisive break, celebrated as decolonization and national reunification. Thus, chanting “Viva Portugal” in Goa today carries polyphonic resonances—nostalgic pride for some, painful glorification of colonialism for others.

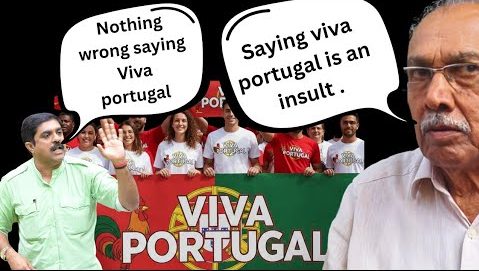

This multiplicity reveals how the slogan has gradually lost its original steam and much of its overt political meaning. Once a performative utterance capable of mobilizing or dividing—whether in revolutionary Portugal or anti-colonial Goa—it now floats as a largely emptied signifier. In contemporary Portugal itself, “Viva Portugal” is mostly benign, a routine cheer at events without urgent ideological charge. In Goa, recent flare-ups highlight sporadic controversy rather than sustained political battle. Some freedom fighters have called it deeply objectionable, an insult to the sacrifices made for liberation, arguing it glorifies centuries of oppression while ignoring atrocities against locals. They urge re-learning history and stricter enforcement of laws against such expressions. Yet these demands often appear anachronistic in the present day. Direct lived experience of Portuguese rule has faded for generations born after liberation; the colonial antagonisms are historical rather than active threats. Diplomatic relations between India and Portugal have warmed significantly—high-level visits, economic ties, cultural exchanges, and pathways for Goans to Portuguese passports normalize the connection. Even gestures welcoming prominent figures of Goan descent underscore pragmatic friendship over lingering enmity.

The act of banning or policing “Viva Portugal” today performs a return to the past, re-enacting liberation-era trauma to police identity and loyalty. It risks freezing Goa in narratives of perpetual victimhood, where every utterance must reaffirm anti-colonial purity. In contrast, those who tolerate or even embrace the slogan—whether through casual use, defense of free speech, or recognition of hybrid heritage—align with a present- and future-oriented perspective. This view sees Portugal not as an oppressor but as a partner in global mobility, tourism, football culture, and shared history. Politicians have questioned objections, pointing out hypocrisy when national leaders engage warmly with Portugal, and linking debates to broader issues like dual citizenship aspirations. Such tolerance signals maturity: acknowledging wounds without letting them dictate every interaction in a postcolonial, interconnected world.

Deconstructing the slogan further exposes its dilution. The signifier has detached from any fixed signified, drifting across contexts without stable reference. Its political potency evaporates because the referents—colonial revivalism, dictatorial nostalgia, or revolutionary fervor—are relics rather than live forces. What persists are fragmented echoes: cultural fondness, ironic usage, or occasional offense, but rarely the unified ideological weapon it once was. Globalization accelerates this neutering; migration, dual identities, and soft power via sports, cuisine, and heritage tourism render rigid binaries obsolete. In Goa, where Indo-Portuguese fusion defines everyday life—from fado-influenced music to preserved forts—the slogan survives more as nostalgic or performative utterance rather than meaningful provocation.

Ultimately, the contradictions within “Viva Portugal” illuminate broader postcolonial dynamics. Time and diplomacy erode once-explosive symbols, turning them into curiosities or flashpoints rather than drivers of action. Banning it revives past divisions without addressing present realities; approving it embraces a multifaceted future where heritage coexists with sovereignty. The slogan no longer carries decisive political weight because the struggles it indexed have receded into history books, leaving behind a quieter, more ambivalent trace of shared yet contested memory. In this sense, its loss of steam is not erasure but evolution—proof that even potent words can fade when the world moves on.